I’ve been breeding horses since I was 17 years old, and I remember most of the horses that were alive at the time. I remember *Witez II, Abu Farwa, even *Raffles, old, with a broken leg. I remember the original Gainey horses, Alice Payne’s Asil Arabians, Jedell Arabians, Whitmore Arabians, and the early Lasma horses, of course. And such horses as Fadjur, Mujahid, Synbad and Radamason.

I remember the well-known horses when I showed Bay-Abi to U.S. National Champion Stallion at Estes Park in 1962, and the other leading stallions when I showed Bay El Bey to his stallion championship win at the Scottsdale Show, back when it was held at the McCormick Ranch. I learned the studbook as my mom and I wrote out pedigrees, and as I saw the horses, I remembered them.

I also was lucky to ride as a kid with a wonderful rancher lady named Syd. I learned correct conformation from her and what made up a good horse. I was in love with everything about a horse; I trimmed the feet of all my horses until I had 28 horses, and no skin left on my knuckles from the rasp when the horses were jumping up and down. I trained my own horses, drove the van, and had tunnel vision about doing my best—and I worried if I could keep things going financially. I have taken my bumps and bruises along the way, had my feelings hurt and wondered when my turn would come to see appreciation for the horses I was breeding.

That is the background to my 10 Commandments of breeding. I give them to you.

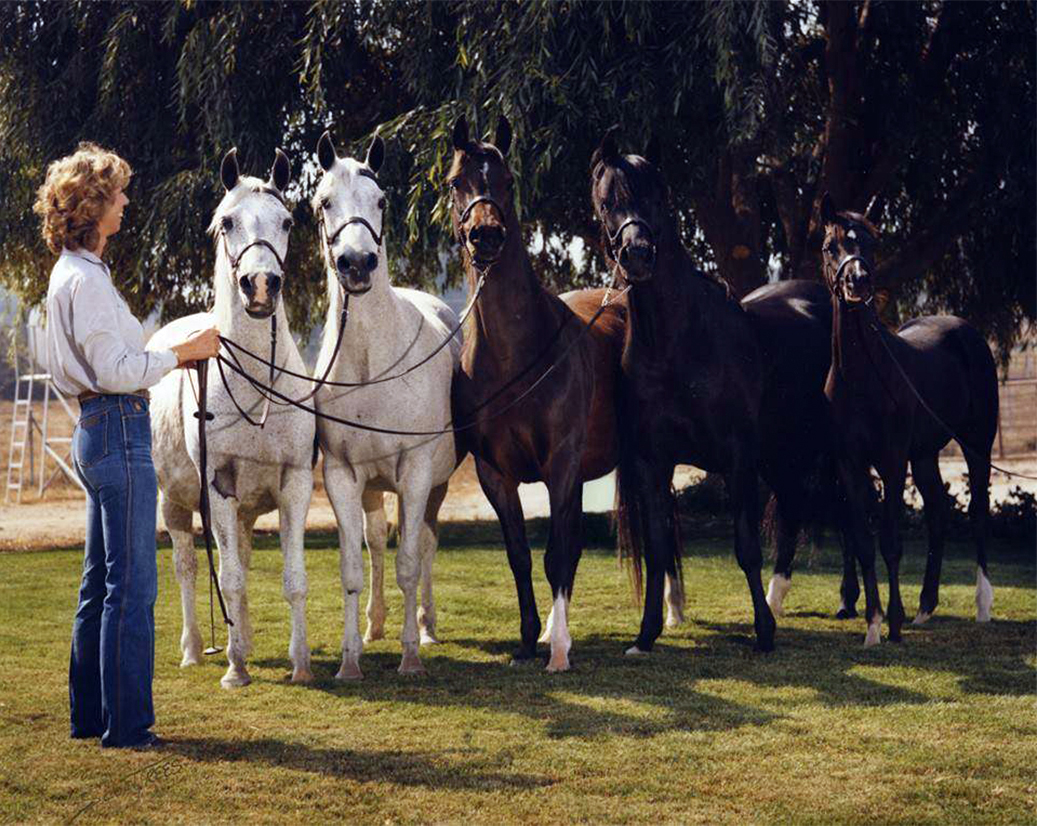

Left to Right: Sheila Varian with *Bachantka (1957) (Wielki Szlem x Balalajka), Baychatka (1965) (Bay-Abi x *Bachantka),

Moska (1970) (Khemosabi x Baychatka), Spinning Song (1976) (Bask x Moska), SweetInspirationv (1981) (Huckleberry Bey x Spinning Song)

#1 – Breed toward your ideal horse. Don’t be swayed by the voices of others. If you have done your homework, in time, others will appreciate what you have accomplished.

Many years ago, in 1961, the fledgling Varian Arabian Farm— my mom and dad and I—imported three mares from Poland: *Bachantka, *Naganka and *Ostroga (another story there). I bred two of them to straight Polish stallions. It was before Lasma brought *Bask to the United States; I used *Ardahan, but the cross was not a good one. I stopped using the Polish stallions that were here at that time on our three Polish mares, and started breeding to my own stallion, Bay-Abi. With that, I got the beginning of a wonderful line of mares from *Bachantka, and when *Naganka was bred to Bay-Abi, she gave us, among others, the kingmaker, Bay El Bey.

People were not particularly nice to me about the fact that I wasn’t breeding straight Polish. I even heard that I was “bastardizing,” that I was merely breeding for the show ring and I would never be a master breeder. It was not a time that I could say, “Yes, but look! What I’m getting is so much better!” So I was quiet, and must admit that my feelings were crushed that anyone felt I was not really interested in breeding good horses.

Now, 40 or 50 years later, it’s not that I care to say, “See, I told you so,” but I would say, “Breed for your ideal horse. Don’t be swayed by the voices of others.” If you’ve done your homework, and I had, others will appreciate what you have accomplished. People need to know this: if you really want to breed horses, then you must stick to what you believe is your ideal horse.

#2 – Recognize that you are breeding Arabians and stay within your interpretation of the breed standards.

Read the breed standards very carefully, because we do have breed standards. They talk about balance and conformation, and horses that have type but that are still useful and conformationally correct. This is most important. So, if you plan to breed Arabian horses that are extremely beautiful to you, and you are following breed type, then you should feel secure in breeding in that direction. You have to feel secure about it—not because of what someone tells you, but because you have done your homework and looked into the standards of our breed.

Sometimes you don’t succeed. There may be a period of time when people disagree with you on what you are breeding, but if you are breeding for quality and you are staying within the interpretation of the breed, there will be others who will find what you are accomplishing worthwhile.

#3 – Breed equally for Arabian type, performance qualities, disposition and trainability.

We tend to forget that all of this goes together to make up an Arabian horse. The Arabian horse is not just type and not just performance; he can’t be just a horse that we pet because he is too difficult or incompatible to accept training. There is no reason in this day and age that our Arabian horses should not have all those qualities. And if not, then you need to address that in your breeding decisions.

Left to Right: Bay-Abi (1957) (Errabi x Angyl, by Raseyn) and Bay El Bey (1969) (Bay-Abi x *Naganka, by Bad Afas)

#4 – Never forget: no foot, no horse.

I’m proud to say that we don’t have navicular at Varian Arabians. I can ride our horses barefoot. We should never forget that no foot, no horse. If a horse can’t be functional, he has no use other than to procreate, and in the long run, the breed won’t survive if we can only look at them. It is such a simple thing. Basically, these horses still need to be able to carry a person.

#5 – Always strive toward a horse of usable disposition, plus beauty. Neither is good without the other.

Today, there is no reason that we have to give up one for the other. There is no excuse for not having a horse that is useful as well as beautiful; you shouldn’t breed for less.

#6 – Follow the lead your horses set for you. The next generation need not be similar in phenotype to the generation before, but each generation must be consistent in overall quality.

Huckleberry Bey was dissimilar to his mother and father, and he was a surprise when he came along—I didn’t know quite what I was looking at, but I kept looking at him, because he was so unique. I waited to see what he was going to become. When he was 9 months old, I knew I had a horse that would offer a different and new opportunity for our breed. And he sired himself in all of his sons and daughters.

Bay El Bey definitely included his mother and father, and while he sired some similarity to Bay-Abi, he also sired differently. As I’ve mentioned before, Bay-Abi was the yeast; he always seemed to take the best part of a mare and himself and put it together.

So, if you have a young horse that comes out of your breeding program that is quite different, but still with exceptional qualities, don’t be discouraged. You may have a diamond that just doesn’t look like the other diamonds. I think that often those animals—the ones that are just different—are the great breeding horses, especially in stallions. You might have a stallion like Secretariat that is so much better than anything else in his breed, yet he never sired another as good as himself. Most stallions don’t; the great ones don’t necessarily sire themselves, but they might sire another step in the line. It just may not be a straight-ahead step. It may go in a different direction. Bay-Abi was a western type horse, very curvy, with a short back, and he sired Bay El Bey, who was 15.2, with a higher-set neck. He was a little more Thoroughbred-y looking; he could have been a great reining horse, and was an excellent English horse. Bay El Bey sired Huckleberry Bey, who was a beautiful English horse, unique to our breed. As a baby, Huckleberry Bey looked like a carousel horse, right off the merry-go-round, all arches and curves. And Huck sired Desperado V, who is strong and husky and very muscular, with exceptional bone and a beautiful face. He is a wonderful working western horse sire, and now is setting standards with his broodmares in halter as well as performance.

There is no breed like the Arabian, which within a direct line has been able to sire horses that can trot as big as our horses can trot and can turn a cow as hard on a fence. Within a line, we’ve gone from the fanciest English horses to the best working cow horses. No breed can do that except the Arabian.

Left to Right: Huckleberry Bey (1976) (Bay El Bey x Taffona, by Raffon) and Desperado V (1986) (Huckleberry Bey x Daraska, by Dar)

#7 – Breed forward. Look ahead. Wonderful new surprises may be awaiting you. Recognize them when they occur.

What I am saying is that if your foal doesn’t necessarily look like its sire or dam, but is of exceptional quality, don’t necessarily discard it. If it still has overall quality, you may have a wonderful surprise. It may be the key to the vault. Huckleberry Bey and Khemosabi are examples of horses that didn’t look like their parents, but were extraordinary individuals themselves and they sired their likeness.

#8 – It is not difficult to improve the produce of a poor quality mare in one generation. It is not even difficult to improve the produce of an average mare in one generation. What is difficult is to improve the produce of an exceptional mare generation after generation. That takes real skill, knowledge, gut instinct, and vision.

Your tail-female line will almost always be your weakest line. This is because often a breeder starts off with an average or poor quality mare and attempts to breed the produce up. You can breed the mare to a better stallion and get a better quality foal, and you can breed that foal to a better stallion and get a better foal.

But if you really want to be sure that you have a program that is going to be consistent as breeding stock, you would like, as a breeder, that the bottom line generation of mares be very, very good.

Left to Right: Moska (1970) (Khemosabi x Baychatka, by Bay-Abi) and Spinning Song (1976) (*Bask x Moska, by Khemosabi)

Left to Right: Sweetinspirationv (1981) (Huckleberry Bey x Spinning Song, by Bask) and Sweet Shalimar V (1990) (Ali Jamaal x Sweetinspirationv)

#9 – Don’t be afraid to appreciate the qualities of others’ horses. Breeding is a competition with yourself, not with others.

Other people’s horses are where you look to see what you may want to add into your program. If your breeding becomes a competition with others, then you will turn away from things you need to include in your horses simply because you are in competition with them. Your mind needs to be open to what you’re seeing, without any feelings of prejudice or envy. If you can keep your mind open and you can appreciate the qualities you would like in your horses, then you’ll have much more opportunity to be successful.

#10 – Consider your horse’s attributes before you consider his/her negatives. All horses have both. It is for you to determine how positive his/her good qualities are before you dwell on the negatives.

We can become so negative about horses that we close our minds to the good parts of a horse. We need to look at the positives first. Then, if there are not enough positives, do not breed that horse. Or if he has positives, but the negatives are too strong, again, don’t breed that horse. All horses will have some negatives; the positives just need to strongly outweigh the negatives, so look for the positives first.

There is one overall commandment for all of us, and that is when we consider buying or breeding to a horse, we take into account not only what will be good for our own program, but what will be good for the breed as a whole. When I bought Audacious PS, I wasn’t thinking just of what my program needed, but also about what the Arabian breed today needed. (When I bought Jullyen El Jamaal, I was in the position of knowing I had to breed out from our sire lines. I was getting too much of the same blood, so I needed an outcross and Jullyen has been a huge asset to us and other breeders around the world.)

Assuming that the stallion you’re considering is of very high quality and has no glaring major faults, I usually say that you need the stallion to contribute at least three things to the breed. Have have great ears (I thought the breed could use better), eyes, and tail carriage—a true tail carriage, charisma, and happiness, carried by a horse who maintains a gentle mind. A good Arabian horse is alert, responsive, willing and gentle, not overly hot and reactive.

We have to remember that we’re breeding an animal that carries on the qualities that came from the desert, and although we have bred the Arabian to be much more beautiful than he was when he was carrying his owner to battle, we need to keep those original qualities—that gentle, strong, sound horse that has made the Arabian the horse of choice for upgrading almost all other breeds for centuries. So as breeders who are seriously considering breeding Arabian horses, we have to take that as an important obligation. We must remember what this breed is about and where it comes from, but continue to look forward to where we are going. That’s the joy of breeding Arabian horses.

When it comes to breeding Arabian horses, friends should not be a part of it. Enemies should not be a part of it. The latest selling price should not be a part of it. It’s simply opening your eyes and letting what you see flow in, unhindered by outside influences.

Everyone tries to make this harder than it is. Sit down and watch your horse in the field until you know everything about it, not in its standup position or in the show ring with its tail over its back, but quietly somewhere, so you can absorb what you’re seeing. Then you must add the style, the charisma, the look—the thing that sets the Arabian apart from all other breeds and makes him unique in the world.

Written by the late Sheila Varian in 2013 ~ may she rest in peace.